Klaus Meyer's Blog

On Global Business and Economics in Volatile Times

My Blog

My homepage

Related Blogs by Business Academics:

-

Michael Czinkota, Georgetown University

-

Margaret Heffernan, University of Bath (Entrepreneur in Residence)

Related Blog's by Economists:

-

Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel prize winning economist, Columbia University

-

Paul Krugman, Nobel prize winning economist, Princeton University & New York Times.

-

D Mario Nuti, Transition Economics, Universita di Roma "La Sapienza".

-

Willem Buiter, Economics & Finance, London School of Economics & Financial Times.

Related Blog's by Journalists:

Globalfocusing Strategy, post Danisco

June 6, 2012

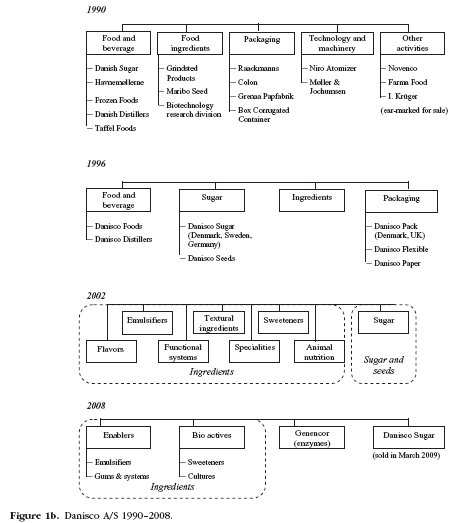

A few years ago I described and analysed "globalfocusing" strategies, the shift of medium-size firms from diversification in a small home market, to becoming a niche player in the global market (Meyer, JMS, 2006; Meyer, SC, 2009). The main idea is that opening of markets due to EU integration and globalization creates pressures on firms that hitherto pursued a diversification strategy concentrated on the home market, to sell peripheral activities and to strengthen the global footprint of their core activity, i.e. globalizing and focusing at the same time.

One of the companies I frequently used as an example has been Danisco, a Danish food conglomerate that became a food ingredients specialist. In spring 2011, Danisco became subject of a take-over battle that ended with its acquisition by American chemicals giant Dupond. A new book (Kongskou, 2012) tells the story of the take-over, and made me reflect over the merits of globalfocusing strategies.

It is easy to say that with open markets, a mostly domestic conglomerate will find itself under attack on many fronts: larger competitors invade their market and financial investors desert them in favour of more focused, and more internationally integrated companies. Companies such as Danisco, GN Great Northern or Nokia thus in the 1990 restructured to globalfocus. But can you effectively change from one strategy to the other. Noka's experience seems to affirm the idea, the experience of GN Great Northern is less positive. However, the main lesson from the experience of all these firms since I studied them is to reflect over the nature of risk that they face.

First, like any acquisition of other firms, the acquisition of firms to strengthen the strategic core of a company is risky: The acquirer may overpay, or may fail to effectively integrate the acquired company such as to create that global niche player they aspire to be. In fact, Danisco needed several years, and a change of CEO, until the newly acquired businesses have been effectively integrated. Likewise, the sell of peripheral units entails risks, both financial and operational.

Second, a more focused company is more exposed to market volatility because it is dependent on one particular industry, and hence to new regulation, new technologies, or new competitors in that particular industry. To some extend this may be compensated by being less dependent on the business cycles of a particular country. But with globally integrated markets, the specialist will in some ways be more vulnerable, and probably its share price is fluctuating more. This is of course not a problem for financial investors who can diversify their risk through their investment portfolio, but it might be a concern for others who are more dependent on the particular company.

Third, a focused company is more likely to become a take-over target. This would be an upside risk for financial investors and for board members remunerated in stocks or stock options. However, some secondary stakeholders in the local communities in which the company is operating may see this quite negatively as key jobs move away from the community. The reason why a focused company is a more attractive acquisition target is that an acquirer - Dupond in this case - is typically looking for a specific business that adds to its existing operations, and they would be less interested in a acquiring lots of associated businesses that have no synergies with their core. Thus, it was only after the sale of the Sugar Division to Nordzucker in 2010 that Danisco became an attractive acquisition target - and that was quickly reflected in the share price.

-

Kongskov, J. 2012. Dansen om Danisco: Med i kulissed ved rekordsalget af et industriklenodie, Copenhagen: Gyldendal Business. (for my book review follow this link)

-

Meyer, K.E. 2006. Globalfocusing: Corporate Strategies under Pressure, Strategic Change 18 (3):195-207.

-

Meyer, K.E. 2009. Globalfocusing: From Domestic Conglomerate to Global Specialist, Journal of Management Studies, 43 (5), 1109-1144.

Who is breaking whose copyright?

June 1, 2012

One fascinating aspect about newspapers in most countries is that they like to report stories where foreigners break 'our' people's copyright, with scant attention to copying done in their own country. Chinese businesses have, for good reason, been in the firing line for copying products designs for both domestic use and export. However, a few weeks ago, a German newspaper reported that almost as many copies of products designs originate from Germany itself, very much to the distress of artists designing new tools, furniture or other gadgets.

Arriving in Denmark, I found a headline translating roughly as 'Uphill Danish struggle against British Furniture Copies'. As background, need to say that Danes are very proud of a number of architects and designers of the 1950s and 1960s, such as Arne Jacobsen. Their designs continue attain premium prices, and they also are major export products sought by fashionable Asian consumers. Now, a British manufacturer is copying those chairs, lamps and other products, and selling them through shops in London and through the Internet (and hence also to Denmark) at a fraction of the price of what they cost in Denmark. "Breach of copyright", shout the Danes. "Perfectly legal", reply the Brits.

The underlying legal issue is that protection for design lasts for 70 years after the death of the designer in Denmark and most other European countries, but only 25 years in the UK. So, it is legal to produce 1960s Danish designs in the UK, but is it also legal to export them? In a long running conflict. Danish courts have ruled that the Brits may not sell their furniture to Denmark because they breach copyright. Yet, how can such ruling be enforced on Internet sales? While the Danish businesses seek ways to enforce the copyrights, the Brits happily sell their copies.

In the supposedly integrated European common market, it is obviously a cause of major tensions if products are legal in one country, but illegal in another. Products flow freely across borders, and copyright holders can't stop them at the borders. Whether 70 years or 25 years is appropriate is a different question, but a common definition of copyrights is necessary to prevent the Brits (in this case) to undercut businesses having to pay for copyrights in their own country.

-

Berlingske Tidende, 2012, Forgaeves dansk kamp mod britiske kopimøbler, May 31, page B12.

-

Berlinske Tidende, 2008, Engelske kopimøbler rykker ind i Danmark, February 8.

Of Lions and Antelopes in Africa

May 31, 2012

There is an old gimmick of consultants to convince their clients to take action (i.e. hire them). I first heard it about ten years ago somewhere in the U.S., but it comes up occasionally, and keeps me annoying more the more I hear it. Today, someone ended his otherwise good presentation with it, I gave him a bit of a telling off - not necessarily making myself popular, but professors don't live from being liked by consultants.

The story goes something like this. "Every morning in Africa, the antelope gets up, and thinks, I need to run faster than the lion to survive. Every morning in Africa, the lion gets up and thinks, today I need to run faster than the antelope because I am my family go hungry. So, tomorrow morning you/your business get up, what are you going to do?" The implication being, that you better run faster, or you will fail ... and hire my services to tell you how to run.

Of course, this is complete non-sense, for four different reasons - an empirical, a mathematical, and two biological reasons. Empirically, when I did a photo safari in Africa, once upon a time, I never saw lions running - they were all lying lazily enjoying the sunshine. Mathematically, the antelope only needs to run faster than the slowest antelope because the lions will only catch one animal - that's enough for a meal.

Biologically, firstly, lions are night-active animals, so in the morning they either digest last night's catch, or they recover for a better catch next night. Secondly, antelopes can always run faster than a lion except for very short distances. So, the only way for a lion to catch an antelope (unless it is injured) is to approach them as carefully and invisibly as they can, and then jump. If the antelopes - who always move in large groups - smell the slightest danger they run, and the lion is left hungry.

There management implications here, but they are different than how the consultants tell it.

-

Firstly, don't run all the time, because you will soon run out of steam, which makes you an easy catch even for an aged lion.

-

Second, if you are an antelope (i.e. someone potentially be chased) you need to a) be very alert for what other do, and b) keep yourself fit for quick and decisive action if and when you need it.

-

Third, if you are a lion (or a challenger in a new market), design a 'blue ocean' strategy that allows you to grow your business without tackling your competitor head-on.

Next time you hear this story, ask the consultant to do the running, and you just wait...

When people don't trust their own kind

May 26, 2012

Most people in most places have a tendency to trust their own kind more than they trust newcomers or outsiders. This can be quite annoying for 'foreigners', and in worst case lead to ethnocentrism and nationalism, and it speaks for the progress of a society if such prejudices are overcome.

However, when it turns around and foreigners are trusted more than people from your own country, then a society has a serious problem. Last night, I talked with people in a pub in London, and the conversation turned to the lousy education system - outside elite institutions - in the UK. Most telling, someone suggested, is that British people prefer to hire a Pole plumber or Romanian builder to fix their water pipe or other repairs in their home, rather than a fellow Brit. Everyone agreed with that observation, surprising as it is for outsiders. Underlying this attitude is the poor (or non-existent) vocational training system, and the poor education of most state schools. On the other hand, immigrants often represent the more entrepreneurial and above-average educated of their home countries. So, the image of the Polish plumber is admired by home owners, but feared by the low-skilled. Sadly for the UK, noone is putting up serious amounts of resources to address this issue.

In China, I noted a similar phenomenon. When it comes to products like medicines, cosmetics, or processed foods, the imported brands are trusted more than local brands, and the same applies to safety-sensitive products from locks to cars and lifts. The underlying issues are slightly different: Scandals have undermined the trust in local brands, and foreign brands are considered more prestigious. Low reliability of local produce is in part a result of poor labour qualifications, but in part also due to big profit opportunities in combination with weakly enforced regulation and consumer protection. Luckily for China, these problems are being recognized, and local entrepreneurs strive to created brands that will be trusted.

Could Germany do more to help?

May 24, 2012

Germany has come in the firing lines as crisis-hit countries look for scapegoats for their woes. Is the current crisis of the euro in part Germany's fault? Could do Germany more (in addition to sending money of unprecedented scale for the shared rescue fund)?

To answer these questions, we have to analyze the causes of the crisis. While the banking crisis triggered the crisis in 2008, the euro also faces a fundamental macroeconomic imbalance that makes life hard for Southern European countries: Inflation has been higher in Southern European countries (Spain, Italy and Portugal) than in the North (Finland, Netherlands and Germany) over the past two decades, which weakens the competitiveness of the South vis-a-vis the North. Moreover, many countries underwent major liberalization and labour market reforms in the 1990s, while the South did not. In fact, Germany went through very painful adjustments after a major recession in the early 1990s. However, the variation in the speed of economic reform increased the discrepancy in productivity and competitiveness. Hence, the North is regularly generating trade surpluses and the South trade deficits - and there is no exchange rate mechanism to change that.

This analysis suggests that improving the competitiveness of the South versus the North would help rebalance the trade flows, and help the South. Could the eurozone North (Germany, Netherlands, Finland) do more to address these issues? (1) Paul Krugman in a blog demanded Germany to loosen its own budget discipline and spend more on infrastructure projects. Yes, theoretically, this would have an effect - but it would be slow, and very limited because only a small part of additional spending would be on imports from Southern Europe. (2) 'The North' might allow wages to rise faster than they are currently rising in 'the South'. This would help a little, and in fact it is happening (some German unions recently signed wage increases of 4.5%). (3) 'The North' might allow the ECB to permit a bit more inflation to allow for more flexible price adjustments. Well, at the margin, this might help a little, but only if this results in higher price rises in the North than in the South. My second point suggests that it is happening, so that is encouraging. But loose monetary policy is a dangerous tool that if not handled very carefully can cause major upsets (i.e. persistent high inflation).

So, overall, there seem to be little things 'the North' could do to help 'the South'. However, given the scale of the macroeconomic imbalances, these measures are insufficient to address the core issues. In particular, the share of additional German/Dutch/Finish GDP growth that would go on imports from Italy/Spain/Portugal is not that big. Moreover, a major part of the imbalances has to do the flexibility of labour markets, privatization and liberalization of the economy (e.g. how complicated is it to set up and run your own company). These issues need to be addressed by those countries themselves, apart from policy suggestions and positive examples, there is little 'the North' can help.

-

Krugman, P., 2012, Those revolting Europeans, Blog, New York Times, May 6.

Grexit and other nonsense

May 23

The

scaremongers among the journalists and fringe politicians keep raising

the possibility of a Greek exit ("Grexit") from the Euro

as if it was not just possible, but likely. Yet it is neither. Greece

may default on its debt, its banks may run out of cash - and it may

bring down a few other banks as well. All that is feasible. An exit

from the euro is not - unless a lot of people invest a lot of

resources in doing extremely stupid things!

Firstly, to introduce a new currency, someone has to introduce it - take the political decisions, print the money, distribute it, etc etc etc. The only institution that can decide to introduce a new currency would be the country's government - yet public opinion is 70% to 80% against reintroducing the Drachma, and all the major political parties want to keep the euro - including the left-wing party that came second in the elections earlier this month. They all understand that it would make almost everyone in Greece worse off, and not solve any of the pivotal problems.

Fundamentally, noone in Greece would want to use any new currency because they would know exactly that it will be hugely devalued very quickly. So, perhaps the Greek government could pay government employees in a new currency. What will those employees do: They will run to the money changer as quickly as they can to exchange their drachma to Euros (or Dollars, or whatever). In consequence, the value will spiral down, hyperinflation will take hold, and the economic crises will quickly resemble Russia or Ukraine in the early 1990s (which is much worse than what Greece is experiencing now).

Some journalists seem to think that the EU (or "the Germans") could force Greece out. But firstly, that would require a change in the EU treaties - and every country has a veto on that, including Greece. In some countries a treaty change would even require a referendum. Which politician would go to his people to ask them to penalize another country? The whole complexity of the undertaking makes the very idea absurd. Theoretically,* one could image Greece to be formally expelled from the euro, which implies that it no longer is part of the European Central Bank and other decision making bodies - but Greek citizens would still use the euro (like Kosovans or Montenegrans do). Unless you are prepared to arrest everyone carrying euros in their pocket, you can't force a new currency on a country!

Sadly, the persistent confusion created by journalists and others who obviously failed their basic economics courses is creating fear. That fear drives people to withdraw money from their banks to stuff it under their mattresses, which further weakens the banks, and makes an already horrible situation even worse. A messy handling of the Greek crisis can cause a lot of harm to itself, and to the entire EU. An orderly default may be the least bad option. But the creation of a new Greek currency would help noone, noone is prepared to introduce it, and if it came, noone would want to use it. It is not an option. Stop spreading misinformation!

-

Postscript: * 'theoretically' here refers to economic theory. In legal theory this is not an option because the relevant EU treaties do not allow for a country to be expelled from the eurozone, or from the EU.

Facebook Shares Down, so What?

May 22

The Facebook's IPO on the New York stock exchange received more media attention than most, and now it seems the media seem disappointed that the shareprice doesn't sky rocket. Does it matter at all?

When a new share is traded, "the market" is searching for an appropriate price as the valuation of companies is (almost) always more an art than a science: There are too many unknowns influencing the predicted future profits of the company. In the early days after an IPO, thus, it is unsurprising if the price of the new share is fluctuating more than most. Moreover, the (previous) owners of the company have all incentives to hype up the value of the company through their PR operations to make as much money as possible. The more people believe in the hype, the more likely they are disappointed.

In the case of Facebook, the valuation is made more complicated by two issues. First, there are considerable doubt about the business model: How do you translate the truly staggering numbers of members into revenue streams? Will the advertising-based model really make profits, or will members start to desert once they are fed up with being bombarded by advertisements? Will another revolution wipe away Facebook's idea of social networking like Google wiped out Yahoo search? Moreover there are risks of a legal nature: Are there copyright issues that interested parties dig up now that the company is rich? Are there infringements of privacy that are deemed illegal in some countries? And, last not least, will Facebook be judged to be a dominant player, which would make it vulnerable to unfair competition complaints. All these are risks that make financial investors nervous.

A particular interesting issue are the dual class shares that Facebook uses. They have been quite popular among IT companies in Silicon Valley recently. They are designed to enable to founders to control the company even when outside shareholders hold the majority of the share capital, and essentially make hostile takeovers impossible. This trend is curious because for years if not decades American economists have lambasted dual shareholder structures in Europe and Asia as problem for the efficiency of capital markets, as they create very high hurdles for shareholders wishing to throw out the management. The EU has made dual share structures more difficult, and also in Asia they are under attack. Investing in non-voting shares basically is like investing in the reputation of the controlling owner(s). If you trust their business accumen - here Mark Zuckerberg's - then its fine. If you loose faith in their ability to generate profits, all you can do is sell.

-

Surawecki, J. 2012, Unequal Shares, The New Yorker, dated May 28 (even though I am reading it today on May 22).

-

BBC News, 2012, Facebook shares fall further as controversy continues, May 22.

Local Brand, Global Brand, and Cardiff FC

May 11

The football world of Wales is learning fast about international business. One of the nations top teams, Cardiff FC, has been taken over by a Malaysian investor. The supporters welcomed the news as the investors promised to invest £100m, with an expanded stadium, new players and a new training ground.

However, then they learned that the investor also insisted to change the club colours from blue to red, and the clubs logo from a bluebird to a dragon, support turned into revolution - a successful revolution in fact as the investor withdrew teh colour change. The investors rationale is obvious: He wants to market the team in South East Asia, where a 'red dragon' brand is more likely to appeal to local football enthusiasts. The business model seems to envisage creating a team that supporters in SOuth East Asia support, and thus generate revenues from TV-rights, souvenir sales etc in that part of the World.

The row reminds me a lot of foreign investors rushing into emerging economies in the 1990s, convinced that their global brands and their superior product quality would win local consumers in no time, and local brands would phase out quickly. Well, didn't always happen that way. In many industries - especially culturally bound industries such as food and entertainment people are very attached to their local brands. For example in the brewing industry, global brands have been spreading like wildfire, yet local brands find their quite substantive niches, either under foreign ownership, or from local competitors.

Now multinational from emerging economies who have grown rich, and invest in Europe. Yet, like European MNEs in the past, they lack sensitivity for local attachment to local brands - like the football clubs' bluebird. Strategy consultants often point to the potential of the global brand, consistently established. But globalization also triggers the opposing effect of people becoming even more attached to their local identity. So, in a few decade, we may see a global football league for the global jet-set, and national leagues that people care about locally.

Of course Cardiff FC is already playing on an 'international stage', although they are Welsh they are playing in the English Championship (the second division of English football), which in footballing terms is another country. So, becoming the Malaysian team in the Championship, and perhaps one day the Premierleague would not make that much of a different, or would it?

-

BBC News, 2012, Cardiff City fans to meet on colour change row, May 9.

-

BBC News, 2012, Former Cardiff City captain Jason Perry fears for Bluebirds future, May 11.

Maersk McKinney Moeller (1913-2012)

(1913-2012)

April 22, 2012

Imagine one of the world's most powerful men passes away, and noone notices it. Unimaginable? Well, it happened. The world's media are so focused on easy-to-access English language sources that they miss what is happening in small countries. Last week Maersk McKinney Moeller passed away, and I only learned about it when chatting with Danish executives a few days later - none of the English or German language business press that I regularly read mentioned him.

If you don't know him, as international business student or executive you certainly will have heard about his business, or seen his ships in port. Without container ships larger than a dozen football field, and container terminals that load and unload these containers, global trade could never have grown as fast as it did over the past half century. The Danish company Maersk is the biggest container shipping company, and the biggest operator of container terminals around the world. Building this company has been his achievement, and made him by far the richest man of Denmark.

Recently, his name came up in a completely different context. I was chatting with the head of the American Museum, which is part of the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. We were talking about how museums attract donations to manage their operations. Big donors would usually insist on large acknowledgements in form of posters displaying their brands, so donations really become advertising. Not so Herr Moeller, as he usually known in Denmark. He gave one of the biggest donations, and all you will find is a little plague in a corner of the room. Herr Moeller felt strong affections for the USA, and wanted to repay the debt he felt his country owed to the USA for the help his company and his country received from the USA during the Nazi occupation of Denmark.

The man was not without surprises. Only a week before, aged 98, he appeared at the AGM of his company, where he still was the biggest shareholder, having handed over management control only a few years ago when he was in his early 90s. When the news of his passing spread, share prices jumped upwards. What a surprising way to mourn the passing of a great leader! It seems that investors a) believed that the company put in place a strong management team to run the company without him, and b) as long as he was still around, the company did not dare divest some peripheral activities in Denmark, such as retailing and a minority stake in Danske Bank, that have no synergies with Maersk's core business in shipping, logistics and oil exploration.

April 16, 2012

In my days as bank apprentice, in the first week at work, our head of program, Herr Fecker, shared an anecdote with us that was important to him: One day he was sitting in the bus when in front of him, but without noticing him, sat two apprentices. They were happily chatting about their work, and gossiping about a customer. The next day, he called them into his office, told them what he had heard, and gave them a thorough scolding! The message was clear: Customer data are confidential, and confidentiality is holy!

Recently, sitting and working in coffee houses across Shanghai, I often thought of Herr Fecker and this anecdote. I am surprised how many people - especially expats - conduct their business conversations in a coffee house, including job interviews. Perhaps they don't have offices in the city, and during the quiet morning hours Cafe Costa, Wagas or the Coffee Bean are convenient places for a meeting. The relaxed atmosphere may help putting to interviewee at ease, and thus help getting to know each other. But, but, but! Have you considered that the guy at the other table may be working for your competitor, or be blogging away on his computer?

Most people talking about business in a coffee house are careful not to mention names of companies - their own or their clients. So, the guy at the next table is left guessing. But sometimes a few confidential details slip out. For some reason, many people full of confidence about their business are not good at keeping their voice down either (apologies for stereotypes, but American and Germans are particular bad at that). Remember, like a mobile phone, a coffee house conversations can both annoy your neighbours and inform your competitors!

How to copy German manufacturing success?

April 10, 2012

German manufacturing is the envy of businesses worldwide. Countries with a trade deficit in manufacturing, such as the UK, wonder how they can learn from German businesses; while firms in emerging economies like China acquire German firms in search of brands and technology. Can they succeed in copying the German secret to manufacturing productivity?

The challenge is complex because the foundation of German manufacturing is in a broad qualification of the workforce, not just of the leadership but of the blue color workers who are doing the actual manual work on the shop floor. The foundation of the system of apprenticeships which are based on a combination of in-house and vocational school training for two to three years, along with further qualification to the 'Meister', a vocational qualification that used to be pre-condition to head a business in many crafts, and remains a sought after quality signal. In large businesses, it can also mark the rise through the hierarchy that eventually leads to the boardroom, past university-educated managers. In other words, the secrets to German manufacturing lie in a combination of an education system, career paths, leadership style (task delegation rather than micro-controls) and collaborative employer-employee relations (including employee representatives on boards), which together set the foundations for capabilities and incentives. (Key elements of this system, by the way, are shared with many of the smaller countries of Europe, who also continue to perform well economically)

When British discuss what to learn from the German model, they tend to focus on issues such a labour market reforms of the last decade, and perhaps mention the need for education programs, but rarely appreciating that it is not a specific qualifications, but broad based education system that would have to be copied - which required for more resources from both state and businesses than either the state or businesses are contemplating of contributing. Moreover, a major obstacle is the very hierarchical nature of British organizations with their very distinct groups of blue and white color workers. Karl Marx's concept of 'class' still applies in many British firms. I found this insightfully illustrated in research by Fiona Moore of Royal Holloway, who studied British organizations acquired by German firms. For example, she found that German expat managers were happy to participate in a 'back to the shop floor' program aimed to help building better shared understanding of the organization than their British counterparts. They likely have practical knowledge regarding the basic tasks they are supposed to supervise, and thus can earn respect with the workforce on their terms. On the other hand, despite the importance of formal titles in Germany, they have less 'us versus them' attitudes than British managers who are likely university educated and have no real shop floor experience.

When Chinese companies acquire German firms in search of technology and brand names, I have similar concerns. One underlying motive often seems to be the idea that learning from the German firm will help them raising the productivity of the Chinese operations. The obstacle that I fear many overlook is that just training a workforce for a few weeks under German supervision won't suffice to raise productivity in the long run; and if more comprehensive training is offered, then the Chinese qualified workers will find themselves quickly headhunted by other firms. The second concern is whether hierarchical models of organizations work with a highly qualified, and hence very self-confident, workforce that knows their tasks better than their leaders do, and would resent micro-management. This affects both the relations between Chinese managers and their German employees, and the future of operations in China once they move up the value chain.

The concerns do not invalidate efforts to learn from German manufacturing (or any other success model). However, they call for caution when it comes to expecting quick successes. It is necessary to understand how the system works as a whole, and they develop new systems integrating ideas from the role model (here Germany) with the existing work practices (here UK and China respectively.

-

Moore, F. 2005, Transnational Business Cultures, Ashford; Ashgate.

-

Moore, F. 2012, Identity, knowledge and strategy in the UK subsidiary of an Anglo-German automobile manufacturer, International Business Review 21(2): 282-292.

-

Taylor, M. 2012, Can German business ideas revise the UK economy? BBC Radio 4, March 6.

CSR: Whose fault are low labour standards?

April 8, 2012

When it comes to labour standards among Asian sub-suppliers to global brand names, there is usually a global blame game: Brand owners, like Nike or adidas in footwear, say hat they do what can - notable by introducing standards of engagement that suppliers are suppose to obey. Locals point to the relentless focus on costs that offers them few alternatives but cut corners. Academic economists emphasize that supply and employment contracts are entered voluntary, and hence would only be entered if they offer better opportunities than the next best offer. NGOs sometimes hold firms responsible even for remote sub-suppliers that they didn't even know existed.

In our textbook (Chapter 10), we point to the local perspective with a quote from a Wal-Mart supplier cited in the Washington Post:

“They are the rule setters. Before Wal-Mart only cared about price and quality, so that encouraged companies to race to the bottom of environmental standards. They could lose contracts because competition was so fierce on price. [Now, they changed.] Wal-Mart says if you’re over the compliance level, you’re out of business. That will set a powerful signal.”

The Economist in a recent articles provides a comprehensive update on this discussion, wondering in particular why Apple, despite consistent evidence of low labour standards by its main supplier, Foxconn, seems to be much less affected by consumer pressures than clothing and footwear brands like Nike and adidias. The article summarizes a new study on the impact of brand owners on standards in the upstream supply chain by Richard Lorke of MIT, which seems not yet published. Three of his findings seem consistent with my own reading of the literature in the field:

-

codes of conduct alone have negligible effect on labour practices,

-

helping suppliers through knowledge transfer helps,

-

collaborative relationships with suppliers that share any productivity gains help even more.

In our text (In Focus 10.4), we use an example from adidas to illustrate the second and third point: A study by Frenkel and Scott (2002) compared the performance of two suppliers that interacted with adidias in different ways, and the one being more cooperative also performed better on issues such as employee retention, failure rates, and financial performance.

The fourth point in Locke's study is particularly interesting. He attributes the origin of unsatisfactory labour standards are often in the manufacturers own business models, especially just-in-time delivery, minimization of inventories, short life-cycles, and last minute design changes – combined with stiff penalties on suppliers failing to deliver. In other words, the pressures created by the buyers - companies further down the value chain - combined with asymmetric bargaining power create conditions where suppliers face tough choices between substantial financial loss (loosing orders or paying penalties for late delivery) and pushing their own workforce to work at condition below minimum standards (as set by local law, ILO standards, or contractual commitments).

Looking at Apple's supply chain from this perspective, it is obvious that Foxconn is under enourmous pressure: Large volume of a new product are to be delivered by the official launch date, design changes are ongoing, and inventories are avoided at (almost) all cost because the product value depreciates sharply once the next update becomes available.

-

The Economist, 2012, Working conditions in factories: When the jobs inspector calls, March 31st

-

Locke, R, 2012, Beyond Compliance: Promoting Labour Rights in a Global Economy, New York: Cambridge University Press, in press.

-

S. Mufson, 2010, In China, Wal-Mart presses suppliers on labor, environmental standards, Washington Post, February 28.

-

S. Frenkel & D. Scott, 2002, Compliance, Collaboration, and Codes of Labor Practice: The adidias connection”, California Management Review, 45, 29-49.

Note: C-numbers link to chapters in: M.W. Peng & K.E. Meyer, 2011 International Business, London: Cengage.

September 2013

- Why are the Chinese investing in Icelandic North Sea Oil?(C6)

- Shanghai Taxi Seatbelts, and Law Enforcement Chinese Style (C2)

July 2013

June 2013

- Traditional Chinese Medicine (C3, C17)

- EU Exports to China: Trends C5

- Capital intensive goods in international trade C5

May 2013

- Understanding post-1980s Chinese through their art C4

- Enhancing Relevance of Management Research in Asia

March 2013

December 2012

October 2012

September 2012

June 2012

May 2012

- Of lions and antelopes in Africa C13

- When people don't trust their own kind C3

- Eurozone: Could Germany do more? C9

- Eurozone: Grexit and other nonsense C9

- Facebook Shares Down, so What?

- Local Brand, Global Brand, and Cardiff FC C17

April 2012

- Maersk McKinney Moeller C17

- Interviews in a Coffee House?

- How to copy German manufacturing success? C03

- CSR: Whose fault are low labour standards? C10

March 2012

February 2012

- Why are journals biased against qualitative research?

- Is Shanghai more like London than like Moscow? C1

January 2012

- Cultural Identity: The Sports we Watch C3

- Starbucks: Measuring and Benchmarking Performance C15

- DOWN: Blackberry, Nokia; UP: Apple, Samsung, HTC

- Happy New Year 2012!!!

December 2011

- Predicting the Future 2012

- Amsterdam to Berlin! and London? C8

- 27-1: Why the UK Exit would be good for Europe C8

- No alternative to the euro! C8

- What went wrong with the euro? C8

- European Brand Value in China C12

- The World's Coffee Shops C10

November 2011

August 2011

July 2011

- Limits to outsourcing C4

- Downward Spiral? UK Loosing Equality of Opportunity

- Can engineers really become entrepreneurs?

June 2011

- Culture Matters in Unexpected Ways C3

- European Crises: UK vs Greece C8

- Chinese Capitalism C2

- Estonian Capitalism C2

May 2011

April 2011

- Business in the long run: Beecham

- Alternative Vote System (2): Qui Bono

- Alternative Vote System (1): Changing Dynamics

March 2011

February 2011

January 2011

December 2010

November 2010

October 2010

- Policy Priorities: Denmark versus UK C2

- Understanding Consumers Worldwide C17

- Global Cosmopolitans C1

- Experiencing Organizational Change after the Crisis C15

September 2010

August 2010

July 2010

June 2010

May 2010

April 2010

January 2010

December 2009

November 2009

September 2009

August 2009

July 2009

June 2009

May 2009

April 2009

-

Should the U.S. learn from (the IMF's experience in) Russia?

-

Observations in a Toyshop: The Future of British Engineering

March 2009